There is a reason that phones, tablets, minis, laptops and desktop computers all exist. Each does a different thing. Sometimes only a slightly different thing, but a different thing nonetheless. And with a few exceptions, we use different products and brands as we perform different tasks on these different devices, depending on what we’re trying to accomplish.

There is a reason that phones, tablets, minis, laptops and desktop computers all exist. Each does a different thing. Sometimes only a slightly different thing, but a different thing nonetheless. And with a few exceptions, we use different products and brands as we perform different tasks on these different devices, depending on what we’re trying to accomplish.

If you’re checking your Facebook feed, the difference between doing so on your iPhone, your iPad and your iPad mini isn’t apparent. But if you’re writing a message to a long-lost friend on Facebook, ideally you want to do so via your laptop or desktop, using a tactile keyboard, on the web. (And maybe you even want to write it first using a word-processing application.) If you’re trying to research Twitter trends or simultaneously monitor thousands of tweets, the Twitter mobile app just won’t cut it (not even Twitter’s website will cut it sometimes—just ask Tweetdeck). If you’re gaming, Candy Crush is fine on a phone, but if you want to play a graphics-intensive game, you’d be advised to do so using a heavy-duty desktop machine or a gaming console. Blog posts are easily tweaked on WordPress’s app, but I wouldn’t want to compose several thousand words by plunking them out on a virtual keyboard. I’d never want to watch Gravity on my phone.

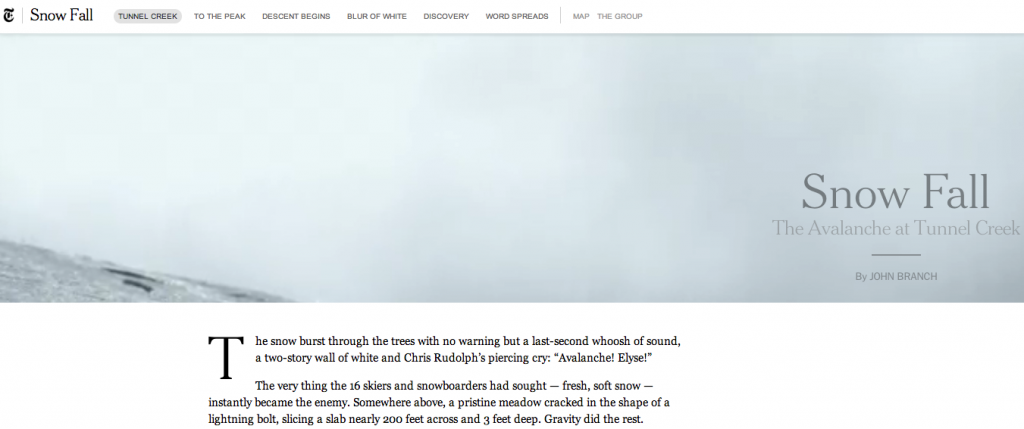

On and on—you get the point. Or, rather, I will get to the point. Magazines are ideally meant to be enjoyed on paper at leisure. The long articles, the beautiful photos, the envy-inducing ads, the feel of the pages in the hand, the tearing out of things to remember. With the exception of some news journalism, very few brands work on absolutely all devices. The New York Times and Buzzfeed, to name two, do an exceptional job cross-platform. But even then, those in-depth, well-reported 10,000-word profiles that the Times does so well? I can’t sit still long enough to read them on the web, let alone while squinting and scrolling on a phone. Buzzfeed’s GIF-sticles? Good luck getting them to load and animate as quickly as you want them to on a tablet.

I’ve written before about how dismally magazine apps perform and tried to propose theories as to why that might be. But maybe it’s simpler than all that. Maybe it’s not more visibility in the app store or better PR or more intrusive update alerts or a consistent user experience. Maybe it’s as simple as: Each task we perform in our lives has an appropriate medium.

Last month, while lamenting the lack of innovation surrounding magazine apps, I wrote:

Jon Lund reported in October that “there’s not much room for magazine apps” on people’s phones and tablets, considering that the average mobile user has 41 apps on his or her smartphone but opens only eight of them daily.

But maybe users stick to those eight apps simply because those are the eight that work best on their phones. Maybe they don’t bother with magazine apps not because magazine apps suck, but because they don’t use their phones to read magazines.

Maybe it’s simply that magazines aren’t truly viable in any meaningful way except for in the form they’ve taken for hundreds of years. (“Meaningful” in a literary sense, but also in the sense of those often-mentioned new revenue models we’re all still waiting to see take shape.)

Of course, some journalism works just great across devices. Quick text-based blog posts, 500-word essays, two-sentence breaking-news alerts—all are welcome, whether I’m on the couch with my tablet, on the move with my phone or at my desk with my laptop.

But in the vast majority of cases, every medium has its best form of distribution—magazines, yes, but also television, movies, books, etc. A place for everything, and everything in its place. So why is the media industry trying to make itself viable across all platforms? Pick a thing, realize its potential, realize its limitations, and do it well.

I previously said that “unlike many apps, the media’s brand relevance and reputation absolutely hinges on an amazing user experience across devices at all times. In short, it has to be perfect.” I stand by that. But if it can’t be perfect—and we’re realizing that it cannot—I don’t think the next best answer is to half-ass a magazine app, a website and the magazine itself. I think if there is any progress to be made, it will be by using technology to focus on task- and purpose-based distribution instead of trying to be all things to all people (and devices).

As I mentioned in

As I mentioned in  It’s human nature to compare things. We put things in context for better understanding. “This thing [business/weather/process/person/event] that is happening is like this other thing that happened, and that thing turned out [good/bad/different/better/worse].”

It’s human nature to compare things. We put things in context for better understanding. “This thing [business/weather/process/person/event] that is happening is like this other thing that happened, and that thing turned out [good/bad/different/better/worse].” Nobody knows anything.

Nobody knows anything.