Fortune media hound Mathew Ingram noted in May 2015, when Facebook’s Instant Articles format launched, that Big Blue saw it as “as a mutual exchange of goods, driven by the company’s desire to help publishers make their articles look as good as possible and reach more readers.” He went on to say:

Fortune media hound Mathew Ingram noted in May 2015, when Facebook’s Instant Articles format launched, that Big Blue saw it as “as a mutual exchange of goods, driven by the company’s desire to help publishers make their articles look as good as possible and reach more readers.” He went on to say:

But whenever you have an entity with the size and power of Facebook, even the simplest of arrangements becomes fraught with peril, and this is no exception. Why? Because a single player holds all of the cards in this particular game.

Around that time, Gawker’s Nick Denton, since brought low by a multimillion-dollar lawsuit loss you may have seen coverage about, went so far as to call the Facebook-publisher relationship not a distribution partnership but “abject surrender”:

So many media organizations are just playing to Facebook. They’re just catering to the preferences…expressed in some algorithm that nobody understands. It’s almost like we’re leaving offerings for some unpredictable machine god that may or may not bless us.

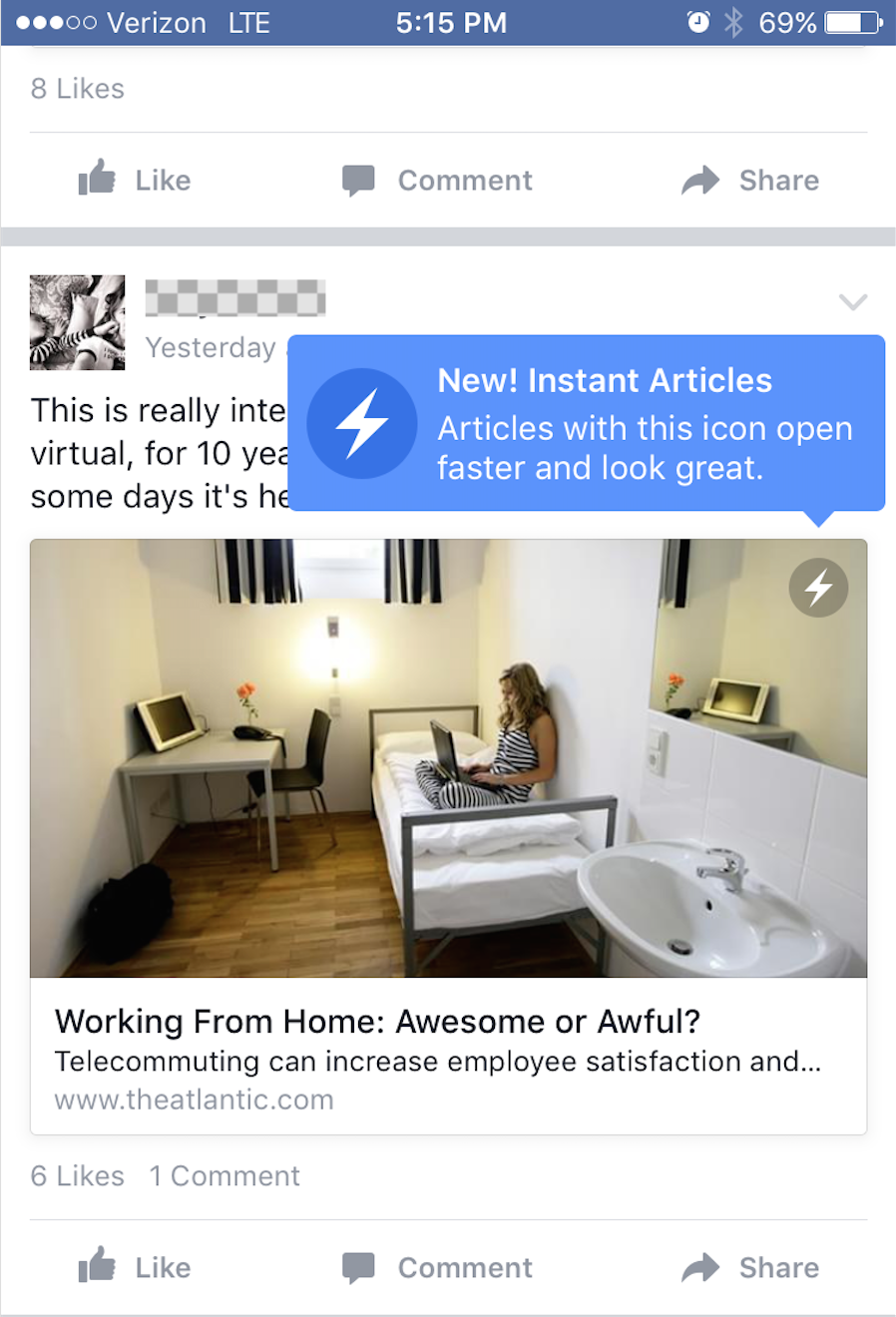

Almost a year after its launch, and a year’s worth of tweaks to the Instant Articles product, we have a more complete picture of the pros and cons.

Pros

Massive distribution open to many publishers

Following its closed launch with a limited amount of “partners,” including the New York Times and National Geographic, Facebook has opened the program to publishers big and small, in the U.S. and around the world, “giving every news organization the capability to publish their content on the social network,” according to Poynter.

WordPress plug-ins make it easier

After a rocky launch that required programmers to reformat every article especially for Facebook, the company was able to scale it to most new organizations through a WordPress plugin the company created, “essentially greasing the skids for mass adoption of the program among news organizations.” Per Poynter:

The plugin is being built in partnership with Automattic, the parent company of WordPress.com, and helps translate news stories to Facebook’s Instant Articles format. This removes a significant hurdle for news organizations.

New potential revenue streams

It’s no secret that magazines are continuing to fold and even digital-native sites can’t make the numbers work. We’ve also seen the rise of ad blockers and native/sponsored/branded content. Are content partnerships like these the answer, or at least an answer?

Cons

Only certain companies are seeing real benefits

BuzzFeed and Vox, to name two, are on board with the new format. Vox even hired media heavy hitter Choire Sicha to oversee its distributed partnerships (Facebook, Snapchat, Apple News and others, presumably). Per the WSJ, “Vox Media has long counted its own content platform as a key to its success. But now it says the future lies in platforms run by others, so it’s bringing in a digital media stalwart to help strengthen those ties.”

But others have yet to make hay from Facebook’s sunshine. As Fortune notes:

The media industry is in a “get big or go home” phase.

BuzzFeed and Vox are big, so they can play in Facebook’s Instant Articles world better than the smaller guys can.

It’s difficult (and costly) to track the audience

As AdAge reports, publishers have to pay more to track their audiences on distributed platforms. Yes, they get bigger distribution (theoretically, anyway), but ComScore apparently charges “$15,000, per platform, per year, to add tracking capabilities.” And six months post-launch, Apple News still doesn’t even have ComScore integration. This puts publishers in a tough position: In order to help their bottom lines, they want to reach the audience wherever the audience is, but doing so costs money they don’t have.

It’s not clear that publishers make money

Following on the point above, in the distributed content ad model, if you don’t know how much audience you have, you also don’t know how much revenue you stand to make. At this point, publishers are still crossing their fingers that this translates to revenue.

Jobs continue to be cut but not added back

Publishers are “re-allocating resources to build teams that produce content for specific social platforms,” per AdAge, but they’re cutting far, far more than they’re adding. Journalism is going through the kind of massive…transition, disruption, sea change, slaughter, whatever you want to call it, that is epic in scale. There are too many outlets that have closed up shop or gone through major layoffs to name. It’s especially chilling when digital-only publications like Mashable, IBT and Slant (just in the past couple of weeks) can’t even make the numbers work.

Distributed content alone isn’t going to save publishers. Maybe a combination of distribution, ads that escape blockers, native/sponsored content and cutting more staff will help. Also? Prayer. Honestly, prayer seems to be publishers’ main strategy at the moment: Please, Facebook and Google, don’t change your algorithms. Please, Snapchat and Apple News. Please, BuzzFeed and Vice. Please, someone figure this out for us. God bless us, every one.

It’s too late to be timely on this, considering January is now over, but I finally read Mat Honan’s Wired piece about media start-ups. I’ve called out some key passages below, but the highlight of

It’s too late to be timely on this, considering January is now over, but I finally read Mat Honan’s Wired piece about media start-ups. I’ve called out some key passages below, but the highlight of  Image:

Image:  The Daily, News Corp.’s general-interest iPad news product,

The Daily, News Corp.’s general-interest iPad news product,  Nobody knows anything.

Nobody knows anything. SF Weekly recently published

SF Weekly recently published